IN 1964 THERE WAS A RAGING DEBATE in my four grade class regarding the relative merits of The Beatles vs. The Rolling Stones that split into distinct camps. Girls tended to fall for The Beatles’ cute looks and upbeat charms while boys were more attracted to the coarser sound and nasty demeanor of The Stones. Moreover, so-called ‘good kids’ tended to prefer The Beatles while the ‘bad kids’ were won over by The Stones’ more rebellious proto-punk stance.

Being basically a good kid myself, but one who preferred cool guitar riffs to mellifluous vocal harmonies, I gravitated toward The Stones’ first album, The Rolling Stones (England’s Newest Hit Makers), which featured their revved-up, hard-edged covers of Buddy Holly’s “Not Fade Away,” Bobby Troup’s “Route 66,” Chuck Berry’s “Carol,” Rufus Thomas’ “Walking the Dog,” Howlin’ Wolf’s “Mona” and Slim Harpo’s “I’m a King Bee,” all punctuated by Keith Richards’ stinging guitar licks and Mick Jagger’s snarling, defiant attitude. The stuff on Meet The Beatles! (“I Want to Hold Your Hand,” “I Saw Her Standing There,” “This Boy” and a sappy cover of Meredith Wilson’s “Till There Was You” from The Music Man) was romantic fluff by comparison.

But there was a price to pay. I distinctly remember a school cafeteria incident: While waiting on line to get my portion of mystery meat and green bean surprise, a kid in sixth grade was conducting his own personal poll by going down the line and confront each kid with, “What’s your vote? Beatles or Stones?” While most kids instantly responded, either out of fear or fandom, with, “The Beatles,” I felt a sense of honor in waving my banner for The Stones, at which point the bully punched in the stomach, knocking the wind out of me. Though doubled over, I stood by my belief — The Beatles were sissies, The Stones were boss.

Nearly 25 years after that lunch room encounter, I found myself face-to-face with Keith Richards, The Stones’ riffmeister himself, in the midtown Manhattan office of his publicist. I was interviewing him for an October ’88 cover story in Pulse! magazine, which was distributed for free in every Tower Records store across the country. Keith and lifelong writing partner Mick had endured many celebrated rifts throughout the Stones’ odyssey and at this particular time were enjoying a trial separation, of sorts. Keith had just come out with Talk Is Cheap, his 1988 solo debut project. Mick had already debuted his own solo project, She’s the Boss, back in 1985. And while both were solid albums, neither was charged with the magic created by the chemistry of the two of them writing together.

The Rolling Stones reunited for several mega-lucrative album/tour packages since the time of this interview, including 1989’s Steel Wheels/Urban Jungle Tour, 1994’s Voodoo Lounge Tour 1997’s Bridges to Babylon Tour, 1999’s No Security Tour, 2002’s Forty Licks Tour, 2005’s A Bigger Bang Tour, 2012’s 50 & Counting Tour, 2015’s Zip Code Tour, 2019’s No Filter Tour and the upcoming Hackney Diamonds Tour, which kicks off in Houston in April, 2024. But at the time of this interview, Keith sounded somewhat dubious about the future of “the world's greatest rock ’n’ roll band.”

And while this interview from 35 years ago -- originally published in Pulse! and later reprinted in my 1998 book Rockers, Jazzbos & Visionaries (available at billmilkowski.com/books) may contain some dated references, like Keith pointing out how “the whole CD thing is fairly new,” his attitude about making music and what constitutes good rock ‘n’ roll probably hasn’t changed that much since then.

Midtown Manhattan, AUGUST 25, 1 9 8 8

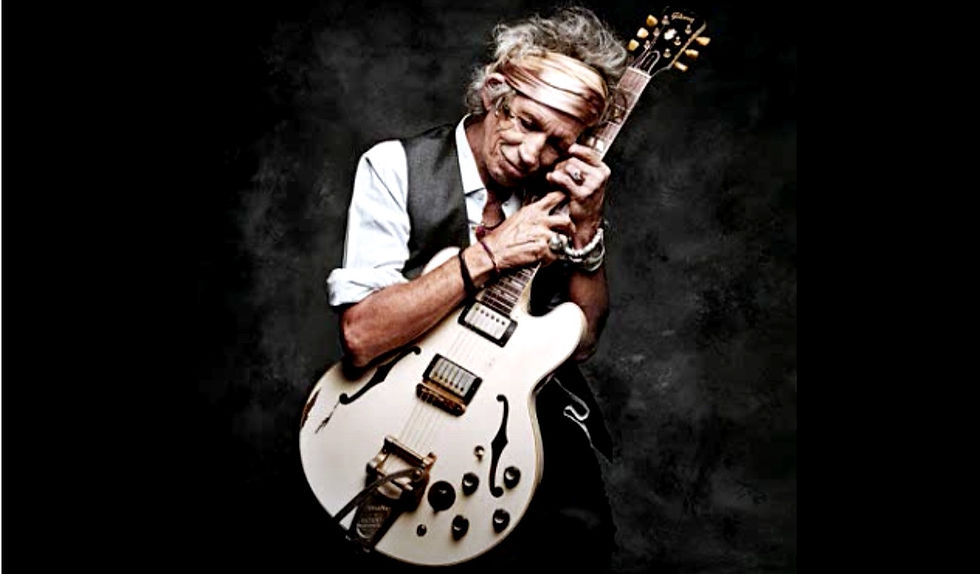

Our designated appointment was for noon. But that relatively early call didn’t stop the legendary Stone, looking as ravaged as all the jokes say he is, from dipping into a bottle of Jack Daniels. So we imbibed, sipping and chatting about Keith Richards’ first solo project after being so intimately associated for so long with long-time writing partner Mick Jagger. Like Gamble & Huff, Leiber & Stoller, Lennon & McCartney, the names Jagger & Richards are indelibly tied and enshrined in rock ’n’ roll’s Hall of Fame. So it was no small feat for Keith to sever that tie and strike out on his own for the first time since The Rolling Stones formed back in 1962. Several cups of Jack into our interview, Keith was feeling no pain and looking forward with great enthusiasm to the release of Talk Is Cheap and subsequent first tour as leader of The X-Pensive Winos, his working band.

The new album prominently features your signature catchy licks. There’s like five “Start Me Ups” on there.

Well, it’s like not surprising. I can only play one way. It’s just a matter of coming up with something. It might have had something to do with the fact that I wasn’t making a Stones album and I decided to write new stuff entirely. I didn’t want to have any hangovers with old songs I had written for The Stones that didn’t come out, which I’ve done over the years. I might hold onto a song for four or five years before we actually record it just ‘cause it’s not right yet. So I made a clean break with that material I had been working on before, and maybe that has something to do with it. I mean, if I’m gonna do a Keith Richards album, I didn’t want any hangovers into the other guys. Which is why, apart from a Mick Taylor solo, there’s no Stones or anything on this album. As much as I love to work with ‘em, I just like to keep it separate.

How did you go about tackling this solo project without any of The Stones on board?

I said at the beginning, if I’m gonna make a record, who am I gonna play with? If I ain’t gonna have Charlie Watts for the first time in 20-odd years, what am I gonna do? To me, that’s a big thing. The drummer is so important in the band. But with Steve Jordan, I had a basis for something to build on.

But you had played with other drummers before, like the New Barbarians tour you did in 1979 with The Meters’ drummer Zigaboo Modeliste and bassist Stanley Clarke.

Oh yeah, I played with some great drummers like Zigaboo, but the idea of making my solo record and not playing with Charlie Watts — it was hard for me. I didn’t even want to ever make a solo record. To me, it was something you did if you had nothing else to do. Until I got into it, and then I started to really enjoy it. It turned me on a lot and gave me a whole different perspective and I found out a lot about other musicians in the process. In The Rolling Stones, you’re in a bubble and the rest or the world sort of goes around it. But inside the bubble, things don’t really change that much. That’s the inevitable thing and it’s been that way for so long. It can almost ignore the rest of the world if it wants. When The Stones don’t want anything to do with the rest of the world they can actually retreat. It’s not necessarily a good thing but it’s easy to stay inside the bubble and let everything happen around you. Usually that means you do your bare minimum. You just sort of go with what you know and never push a little bit more. And that’s understandable. Anybody who is that successful and didn’t expect to be, but they were and they are…there's a sort of laziness that sets in, I guess. So I learned quite a few things by working outside of this bubble and looking at the world from a different perspective.

So you’re having a naughty affair right now.

Yeah, in a way. And if it helps to kick The Stones up the ass too, then that’s fine. Then everything's been passed along as it should be.

Has Mick heard this record?

Yeah, Mick's heard it a couple of times. [pause] Talked all the way through it, though. But then he talks all the way through anything. As far as I can gather, from what I hear, he likes it. Mick and I are still sort of testing each other out at this point. But I love the guy. I love to work with him. There are certain things about what he’s done

that piss me off, but nothing more than what goes down with any friends, really. If you can’t lean on your mate then you’re not really his friend, right? If you don’t say, “I think you’re fucking up, man,” then you’re an acquaintance, not a friend.

Is there any underlying meaning behind the tune “You Don’t Move Me”?

Yeah. [laughter] I guess! To a certain point. It was a kick-off point, in actual fact, to write about Mick. As I got into writing the song it became about any situation where you’re put into that sort of conflict. But yeah, it was a kick-off point. I can lie to you and say there’s absolutely nothing to it, I never thought of that. But the honest truth is, of course, it was a kick-off point. You know, when you’re pissed off at somebody, you’re pissed off at somebody. But it’s not solely about Mick.

How did he react to it?

I don’t know if he’s listened to it. I mean, he’s heard it but I don’t know if he’s really listened to it. I’m sure he won’t enjoy the actual meaning of it. But look, Mick and I go a little bit beyond just being able to insult each other. I mean, we’ve known each other for 40 years. It’s not just two rich superstars indulging in a power struggle. It’s not really about that at all. It’s about us trying to find each other at this point. I think maybe what we found out is that without knowing it, Mick really needs The Rolling Stones more than actually The Rolling Stones need Mick. We all love the band but I don’t think Mick thought that he needed The Stones, and he’s probably just realizing that now, which is why we’re putting the band back together — at his request, not mine. And I think it’s a very astute move. But I do hope that it’s not just a rescue attempt. I would hope that he wants to do it and realizes that he’s gotta get back into it strong. See, this thing’s gotta grow up. It can’t just go backward and compete with some other new recording stars. It’s got nothing to do with that. It’s got to do with carrying on your life and growing up and making it work. And to me, that’s the most interesting — the only interesting thing — about it. Can it be done? Can you actually be a rock ’n’ roller for this long? I played with cats who were just as powerful the day before they died, Muddy Waters being one. It remains to be seen if that will hold true for either Mick or myself.

Most people don’t know if you guys love each other or hate each other.

Nor do we! Mick and I have always been able to work together no matter what we thought about each other at certain points. To me, this is an interesting time. I’m 45 years old. There’s a point in your life where you have to reassess things. It happens to everybody. It’s happened to our relationship, so now we have to see if we can get over it. Sometimes I’m not a great help, other times he ain’t a great help. But we’re still trying.

But for the moment you’re taking a break from The Stones. And in spite of what directions you might go in with the X-Pensive Winos, your signature sound still cuts through and is instantly identifiable. Maybe it’s because you don’t use many effects.

Maybe that has something to do with it. But I can pick up any guitar and immediately get that sound. I know it must be a particular way of striking the instrument, I guess. I call it heavy-handed when I want to be modest.

There’s a lot of people like that. Albert King comes to mind.

And somehow it always sounds like him. I don’t know, there’s just certain styles of playing that you do play in your own way. Maybe it’s in the way your fingers bend, for all I know. And so whenever you pick up the guitar it's not so much the sound of the instrument itself, it’s like the thing that you add onto it — the attitude.

Obviously the production values on 'Talk Is Cheap' have changed a lot since the first Stones albums, but your approach to the guitar is still the same. It’s a direct and very intuitive thing.

Yeah, I wanted to keep it very basic. And I thought if I'm going to start doing solo albums I want to keep at least the first one very straight ahead and just get into it with a good band. To me, the most important thing is finding the guys to work with. That was far more important to me than the songs, at the time — to find myself a bunch of guys who can feel and sound like a band.

How did that come about, through intensive rehearsals?

Well, it happened in a very natural way in the beginning of ’86, I suppose…whenever The Stones’ Dirty Work came out. I originally planned to take that out on the road in much the same way like Some Girls was done, for instance. Dirty Work was an album that was specially built for a tour, so it was a two-part thing. And when that didn’t happen, I suddenly found myself on the beach in a half daze, so to speak, with nothing to do, suddenly, when I was expecting to do something. And at the same time Steve Jordan found himself in the same situation. We’ve known each other for a few years and had gotten to know each other real well the year before. He just hit the same point in his career. He had left the David Letterman Show for whatever reason, and then the Aretha Franklin track came up [a remake of The Stones’ “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” on Franklin’s 1986 Arista album, Aretha]. They wanted to record in Detroit. Well, I know the song and I love Aretha, so I thought, “There can’t be any problems doing that. It might be fun.” So Steve came along and we did that track together. That was the beginning of our musical connection. After that, we did the Chuck Berry movie together [the 1987 documentary, Hail! Hail! Rock ’n’ Roll]. And throughout that period of getting to know each other I also got to know guys that he worked with like [bassist] Charley Drayton. And through doing the Chuck Berry movie, I met [NRBQ bassist] Joey Spampinato, who is on a couple of tracks on this new album of mine. [Guitarist and session man] Waddie Wachtel is someone I always wanted to work with, for years and years. We had done a couple of sessions together, though I don’t think they were ever released. But we said, “Sometime we gotta do something serious together.” That was a long-standing arrangement. And Ivan Neville I’ve known for quite a while. He’s played bass on Stones tracks before. He’s such an all-around-er. So the challenge was to put them all together and make it feel good. Everybody just fell straight into it and within a week we had a real band.

I remember hearing over a year ago that you and Charley Drayton and Steve Jordan were jamming up new material together.

Yeah, we were rehearsing way downtown. I guess we started very early last year, February or March [1986]…somewhere around then. Just putting guys together and putting songs together.

You don’t compose your stuff at a keyboard?

Naw! I can't walk into a place and say, “It goes like this.” Songs, to me, come through osmosis. The bass player will feed you something that takes the song in a whole new direction or you’ll stop for a bridge and somebody will come up with a good idea. “Ah, hold on! That note there gives me an idea!” Or somebody makes a mistake and stumbles onto something new. To me, all the best songs were basically beautiful accidents.

I remember seeing Dr. John at a session where he was struggling to bring in a tune under four minutes. Finally they did a take and there was a lot of excitement in the room afterwards, until they looked at the clock. The song came in over eight minutes! But everybody in the room agreed, “That’s the one.”

Yeah, that’s the magic. It happens very suddenly and then it’s a matter of just recognizing it, or having a good guy in the booth who recognizes it. I always leave the tape running all the time, just in case. Even when someone’s taking a shit, I leave a two-track running all the time to get the odd ideas. And often in those bits you get an extension of a song that you wouldn’t otherwise get if you were just sitting down and nailing what’s on paper. I’m the reverse. I prefer to find the music by playing with the band. But now and again things happen the other way. I wrote “Satisfaction” that way. You suddenly wake up with an idea and there it is! So now I always have a guitar and a tape machine handy by my bed in case that happens again. And it doesn’t happen very often. You wake up and you know exactly how it should go as long as you can put it down right there and then. It’s like a dream, you know? Sometimes I’ll come up with some brilliant song or melody while walking along and by the time I get home it’s totally gone. After a while, it always comes back, once it’s in there [points to his head]. And sometimes it might be years, other times it might be a week or a day. You can never tell. Eventually, nearly all of them come back.

Did any of these tunes emanate from the lyrics or did most of them come from the music?

Luckily, most of them come in the way I like them to come, with the hook and the riff together, then fill in the verses later on. A good example of that on this new album is “You Shouldn’t Take It So Hard.” That hook came at the same time as the riff. And invariably you’ll find that when that happens the alliteration and the rhythm of the words is ten times better than if you try to force or wedge a line in there. If you have to think a line up separately to make a hook, it never seems to me — maybe because I’m on the inside looking out from the other way — but to me, there’s always a certain discomfort with that. Most of these hook phrases — “You Shouldn’t Take It So Hard” or “It’s a Struggle” — they’re all very mundane slogans. They’re the things that people say every day. You can hear “Make No Mistake About It” every time you watch a tennis match. Clifford Drysdale [South African former tennis pro and longtime announcer on ESPN] will always say, “That’s a sure winner, make no mistake about it.” I mean, I was starting to hear all these titles coming back at me from ads on TV and from the weirdest areas, just things that people say. You just give it a slight twist and you’ve got a hook. Working with Steve Jordan, we fell into that a lot We didn’t expect to write this thing together but I know that I need to work on songs with somebody else. I’m not particularly interested in writing songs on my own. If one or two come like that, that’s fine. But I enjoy sitting around with someone, paper strewn wall-to-wall, kneeling down, scribbling away, and flashing off of each other. And the more we got into it, the more we realized we didn’t need a producer or anybody else. We didn’t need to bring in anybody else to bounce off of. That was the way I wanted to do it. I also did spend a few days with Tom Waits, just knocking a couple songs together. I’m really interested in his work and it’s fun to sit around and write songs with him. But there’s nothing on this album connected with that process. It might be on his album, for all I know. It’s like, “Well, it’s yours or it’s mine.” Whoever’s got room, you know?

The production on 'Talk Is Cheap' is really loose.

It’s all soiled by human hand, you know?

It certainly goes against the grain of what’s happening in the industry now with technology taking over record production.

In a way it kind of is. There’s a certain spirit to me that’s lacking in an awful lot of what goes for rock ’n’ roll records these days. But then, I'm getting old so maybe I’m starting to get reactionary. I never quite trust my own judgment, especially when I just finished a record. Because you’re so far into it that in a way you’re too close. Even with most of The Stones work, I don’t remember listening to the music that intently in that gap between finishing a record and it coming out. I usually take a real breather from it. And actually with this one it’s strange…maybe just because it’s mine. I don’t know if I’m vain or what but I find myself listening to it over and over again throughout the day. And it feels good. Usually when you've finished something, you gotta get away from it, no matter what you think about it. But Steve and I feel pretty good about this album.

The cycle always changes. People eventually get sick of being inundated with over-produced albums. And if that’s what is happening now, this album is going to sound fresh by comparison.

Hopefully, yeah. It’s not something I planned on. It’s not an underlying cause for this album. It’s a hope for it. If it just persuades a few people, I’ll be happy. We’re just trying to make records with a bit more of the human touch rather than pushing buttons on drum machines and synthesizers. There are so many toys on the market and everybody's playing with them. But there's no dynamics in that. And, after all, rock ’n’ roll is really about interaction. It’s got so much to do with that. Rhythm and dynamics are really the basis of rock ’n’ roll — the only two areas where you can really be interesting. It’s not the actual notes and the chords; God knows they’re simple enough, right? I mean, you have to keep the melodic content down to a minimum as compared to other kinds of music. Trying to be innovative in that area then, coming up with a slightly new melodic twist in rock ’n’ roll — that’s a very hard thing to do because it’s very limited music in that respect. But in terms of rhythm and dynamics, all the world’s wide open. And to me, that’s what making records is about, that indefinable thing that you can’t find on any meter in the studio. When you’re making a record, it's about what's going down on tape. And really you’re looking for that incredible thing that making records can do. You can actually put down a feeling that will come off, an actual spirit, an indefinable thing. There’s no way it should be able to get on there but it can and it does. It’s an incredible medium.

All the albums that you've been involved in where there’s another guitar player, whether it’s been Brian Jones or Mick Taylor or Ron Wood, have this quality of production where the guitar tracks are so intermeshing that it’s hard to separate them.

That’s what I’ve always liked about guitar records — when they start to go through each other to the point where it’s not important who’s playing what. There might be an interesting tension going on from one guy to the other and that goes straight to the people, in that respect, if you’ve got it on tape. And it’s those moments that are worth capturing, not these set-up poses. That’s what I’ve always loved about early rock ’n' roll records, that tension and energy that came through those speakers. Before I was into it that much in terms of who was doing this and who was doing that, I was just affected by that overall sound. Just what you can put out of that speaker has always been fascinating to me. Alright, I happen to write songs, make records, and I happen to play guitar. But to me, what I really do is make records. That's what I enjoy doing and what I think I’m probably best at. And that’s a combination of all those things, but it still fascinates me. In fact, more and more. I suppose it’s easy to get blasé making records for all these years already. But now I find it even more fascinating than ever.

And you mentioned that in the process of making this album, these musicians really kept you from being blasé.

Oh yeah. And also I realized that even though you try to remain as fresh as you can, inevitably... I mean, 20-odd years with the same band you do fall into certain ruts and certain habits of working. And one of The Stones’ habits was that if I’m knocking out a riff and it’s really working and then I get stuck somewhere for a bridge or something, I’ll stop playing and everybody’ll stop playing. Everybody will put their instruments down and go off. This is one of the luxuries of The Stones. If I stop they all stop, and that means time for a break, knock off for maybe half an hour before you can get 'em back together again. You can’t rush that thing. That’s the way The Stones work. But these guys in the X-Pensive Winos just keep playing. And if I get lazy they’ll say, “Pick it up motherfucker!" And nobody says that to me, you know? [laughter] But then you gotta pick it up, so you just keep playing. So instead of getting ready for the usual break, it’ll be like, “No way! Let's play!” It’s great. I enjoy it.

You sound a lot more confident about your singing on this new album.

Well, I’m getting there. You’d never guess that I was soprano until my voice broke when I was about 13. I was a prized possession for a while — me and two of the other worst hoods in my school. We had these angelic voices. But I didn’t realize really, until I started doing this stuff, how much I had retained from my old choirmaster some 30-odd years ago, all the things I had learned from him about singing. But the voice has changed a lot since I sang in Westminster Abbey. I didn’t really enjoy singing for a long time, but I’m getting the hang of it again now.

What kind of things have you been listening to lately? Are you a record buyer?

Occasionally I go on binges and buy every blues reissue I can find. They’re putting out a lot of good stuff now, all the early Chess recordings. They’ve cleaned it up a lot and I’m not sure if I really like that or not. Sometimes I think I'd like to hear the old hiss along with some of those blues tunes. You’ve got to pick and choose with that. And, of course, the whole CD thing is fairly new. I’m sure they’re going to improve the sound even more in years to come. DATs are already happening. A lot of new technology is being developed and I presume this isn’t the end of it. Hell, I started recording on two-track. Now look at it! But I think there’s so much stuff that it's kind of overwhelming for musicians and listeners alike a bit in the last few years.

So you’re still a blues fan.

Always. You can never get enough of the blues, or Mozart, or great reggae. Although you don’t hear great reggae anymore because they’re caught up in pushing buttons too, nowadays. It really takes all of the expression out of it, as far as I’m concerned. I’m more interested in human expression and how it affects people. To me, that’s the beauty of music. I think it might be a romantic notion but to me music is passed on and on and on through word of mouth. Anybody who plays something knows how much they owe to the guys who went before. And it goes on and on and on, way back to the beginning of time. There’s probably only one song, really. Everything else is a variation on it.

Finally, what would be your choices for desert island discs?

“Little Queenie” by Chuck Berry, "Key To The Highway” by Little Walter Jacobs with Jimmy Rodgers on guitar, “Still a Fool” by Muddy Waters, “Reach Out (I’ll Be There)” by The Four Tops, “Mystery Train” by Elvis, “That’ll Be the Day” by Buddy Holly. Then something by Segovia, something by Mozart, something by Bach, and anything by The Jive Five.

What an excellent trip back in time with one of the truly great icons of rock!